A Movement of Old Lesbians

by Barbara Macdonald

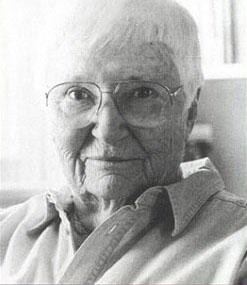

(Following is a cut version of the talk given by Barbara Macdonald at the First West Coast Conference and Celebration by and for Old Lesbians, April 1987.)

Let this be a movement of brave old dykes led by brave old dykes. Age is a time of great wonder — a time when we have to hold, with a fine balance contradictory truths in our heads and give them equal weight; old is scary but very exciting; chaotic but self-integrating; narrowing yet wider; weaker yet stronger than ever before.

It is we who must name the processes of our own aging. But just as we could not begin to say what it means to be a woman until we had confronted the distortions of sexism and homophobia, so we cannot explore our aging without examining and confronting ageism. It is the task that lies before us.